Kyivan Rus'/Ukraine

A Thumbnail History

Ukrainians' forebears of legend are the Slavs and the Scandinavians, i.e., the Vikings, called Varangians in that part of the world. The Varangians became assimilated into the local Slav population and instituted the first powerful dynasty in Ukraine, (or "Kyivan Rus' " as it is historically designated): the Rurik Dynasty. The inhabitants of Kyivan Rus' were called "Rusyns" (NOT "Russians")

While at the peak of formidable power and influence, the Varangian Prince of Kyiv, Volodymyr the Great (Waldemar, in Norse or Scandinavian), patriarch of the Rurikid dynasty, converted to Christianity in 988, and founded what became the Rus'-Ukrainian and, in due course, the Russian, Orthodox churches.

At the time of Yaroslav the Wise, son of Volodymyr, Kyiv was a centre of learning and a centre of trade with all corners of the earth second only to Byzantium; and this, while western Europe was experiencing the Dark Ages.

At the end of the first millennium, these Slavic tribes of Kyivan Rus' that lived in the lands ruled by Kyiv conquered the Finno-Ugric tribes to the north and brought Orthodox Christianity, culture, and a written Slavic language to them. The written language, known as Church Slavonic, became the language of state, church, culture, and trade in those areas, although their native Finnish was not eradicated for hundreds of years. The eclectic Muscovite language is what eventually developed from this mix, which includes also some Mongolian.

Weakened by internecine rivalry between the Varangian princes and lacking unity under the assault of Mongol invasions, Kyiv collapsed in the 12th century and Kyivan Rus split up into separate principalities. The strongest branch of the Rurikid dynasty migrated to Novgorod 1,000 km to the north of Kyiv, to rule over the mix of indigenous Finnish and Ugric tribes there, while remaining in a state of submission and paying tribute to the Khanate of the Mongol Horde.

Those northern lands, becoming eventually an independent princedom, were known by many names, including Suzdal and Muscovy. The name Rus', on the other hand, historically was applied strictly to the Slavic people in what is Ukraine today.

By the 14th century, this remote Rurikid branch was governing the lands to the north of Kyivan Rus' as a state called Muscovy. It held court in the city of Moscow. Feeding on the decaying carcass of the Mongol Empire to which it had been subservient, Muscovy grew strong and became the predecessor of Russia and the Russian Empire. However, it developed in a direction that was politically, economically and spiritually alien to Kyivan Rus'.

In the meantime, under a separate Rurikid branch, from the year 1000 onwards whilst Kyivan Rus' was still at its zenith, the principalities of Halych and Volhyn' grew, in what is present-day western Ukraine and - partly - eastern Poland. When Kyivan Rus' was brought low by the Mongol Horde in 1240 AD, its sundered Rurikid power base not only migrated to the north under Muscovy; it was also taken up in the west. Prior to the destruction of Kyiv by the Mongols, in the year 1200 Prince Roman of Volhyn', with the support of the boyars (noblemen) of Halych, had ascended the throne of Halych and peacefully merged these two principalities into Halych—Volhyn'. This new state ultimately became the western successor state of Kyivan Rus' under the name of Halychyna (Galicia). Its capital was initially Halych and, later, Lviv.

Among the major preoccupations of the princely rulers of Halych—Volhyn' was to secure the realm against the Lithuanians, Poles, and Hungarians, and to protect the country against repeated incursions by the Tatars from the south-east. At the same time, they strove to maintain an uneasy co-existence with Muscovy. In all of this they at first succeeded: under the rule of Prince Roman and, later, that of his son Danylo Romanovich, the united principality asserted itself for a time as a major state in eastern Europe. Over the space of 150 years following the creation of Halychyna in AD 1200, however, the ruling Rurikid princes perished in battle and Roman's dynasty died out. The noblemen of Halych—Volhyn' then elected a Polish prince to rule, and Galicia as a result fell eventually under Polish control by 1359. Thereafter, there ensued a very turbulent history for Halychyna, spanning centuries. Halychyna (and Rus'-Ukraine to the east, as well) was incorporated for a time into the powerful Lithuanian-Polish Commonwealth, and, in a more recent era, Halychyna became part of the Austro-Hungarian empire as a province called "Galicia", while Rus'-Ukraine was occupied by Tsarist Russia.

Polish rule in Galicia and Rus'-Ukraine was characterized by an influx of Polish gentry, and these became the major landowners (magnates) and the dominant social class. Galician boyars were compelled to accept the Polish language as well as Polish legal and social institutions and Roman Catholicism. Peasants, for their part, became shackled to a serfdom little different from slavery under the exploitative Polish gentry, who routinely leased their holdings for whatever profits could be squeezed out under Jewish lease-holders called Arendars. The Arendar had power of life and death over the serf. The latter had no recourse to higher authority before the law. The Arenda Contract is an example of the extreme degradation imposed in that epoch on Ukrainians. The outgrowth of this condition — in time — was a strong Ukrainian nationalist movement, and increasingly effective armed resistance in the form of organized Cossack formations. The latter, in large part, were serfs escaping the Arenda impositions, who thus chose to live as freemen in the (then) boundless and ruler-free steppes in the south of present-day Ukraine.

Although cossackdom was a frontier phenomenon, these escaped serfs eventually rose in a revolt lasting from 1648 to 1654 that shook all of Europe, under the brilliant leadership of Hetman (general) Bohdan Khmelnytsky, and successfully threw off the Polish yoke. This national uprising, the Ukrainian War of Liberation of 1648-1654, freed a large part of Ukrainian territory from Poland and established a Cossack Hetman state that endured until the 1780s.

Meanwhile, to the north, Muscovy was able to grow and steadily expand through aggression. In the 18th century, when they finally gained control of Kyiv and much of today's Ukraine, the state of Muscovy unilaterally renamed itself using the Greek version of the name Rus', namely Rossia. A scholarly commentary on this usurpation may be found here.

Prior to this usurpation, there was no confusion between Rus'-Ukraine in the south and Muscovy in the north. Due to the resulting confusion that this name-plagiarization caused, the Rus', or Rusyny, began calling themselves Ukrainians to set themselves apart from Muscovites-Rossiany. The consequence of this is that the Rossiany have hijacked the history, the glory, and even the name of those they conquered.

Of more recent vintage than the rulers of the Princely era, in the later period the movers and shakers in Ukraine were the Cossacks.

From historian Nikolai Tolstoy in his book Victims of Yalta: "The Cossacks . . . were descended from heroic freebooters who, in the 16th and 17th centuries moved southwards to escape the constraints of their Russian and Polish rulers. They fought bravely against Turks and Tatars, and were rewarded with military and social privileges when in due course the Tsar's authority was extended over them. Their history was checkered and violent. Earlier they had risen in rebellion against the Tsars; later, they were employed by them to suppress revolutionary agitation."

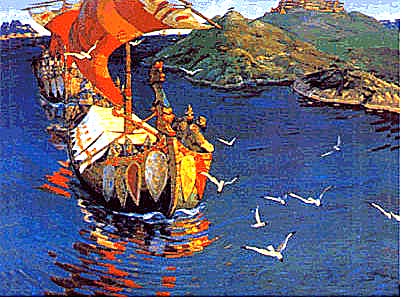

That vignette of Tolstoy's spans three centuries; right up to the year 1918, in fact. The scene shown in the accompanying image is that of Ukrainian Cossacks, in their Khmelnytsky-era heyday, composing at their Zaporozhian Sich military headquarters on the lower reaches of the River Dnieper a defiant, insulting letter to the Sultan of Turkey circa 1660, in reply to his demand that they surrender.

The history of the Ukrainian Cossacks has three distinct aspects:

- their struggle against the Tatars and the Turks in the steppe and on the Black Sea

- their participation in the struggle of the Ukrainian people against socioeconomic and national-religious oppression by the Polish magnates

- their role in the building of an autonomous Ukrainian state.

The distinctive political role played by the Ukrainian Cossacks in the history of their nation distinguishes them markedly from the Russian Cossacks such as those located in the Cherkassian regions.

The Ukrainian Cossacks and related formations constituted a warrior society at one time so powerful that they were able to challenge the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Muscovy and the Ottoman Empire. Hetman Ivan Mazepa, Cossack leader and head of of the Ukrainian Cossack State, is an enduring symbol of Ukrainian independence, for his policy of unification of all Ukrainian territories in a unitary state, and his steadfast resistance to Russian imperialism and expansion that culminated unfortunately in the disastrous (for him and for Ukraine) Battle of Poltava of 1709.

After Poltava, the next opportunity that Ukrainians would have to attempt to seize back their national freedom arose only some 200 years later during World War I, in Galicia/Halychyna in 1915, under Austro-Hungarian rule. The target of their action was not to the west, but to the east, against invading Russian forces. They saw themselves as being chosen by destiny to take up the sword from the failing hand of Mazepa, and in fact their enemies, the Russians, called them Mazepyntsi meaning, followers of Mazepa.

(To be continued . . .)