|

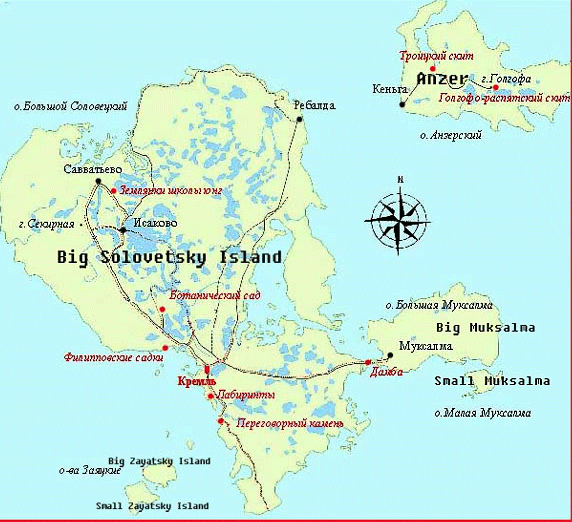

| Click here for larger size map |

This book is about the Solovetsky Islands in Russia, and the tale of one man's survival in this crucible of the Soviet Gulag system in the 1930s.

The Solovetsky Archipelago comprises six islands in Onega Bay, located in the western part of the White Sea at latitude 64°N, covering 347 km². (134 mi²). They are just 1 degree (150 km) below the Arctic Circle, about 300 km (186 mi) west of Archangelsk. The islands, known interchangeably as "Solovetsky/Solovetski", "Solovky/Solovki", or "Solovetsk", are the site of a monastery founded in the Middle Ages. Early in the monastery's history, and then increasingly under the tsars, it came to be used also as a place of exile and imprisonment so that the monks lived, quite incogruously, both as pious hermit-like men of God and as implacable jailers in the service of Muscovy's rulers.

Despite its northerly latitude the microclimate here is moderate, due to the warming influence of the Norwegian Current, a northern arm of the Gulf Stream. Winter temperatures can dip to minus 20°C (minus 4°F) and winters are long and windy, but extreme cold such as at Murmansk or Archangelsk is rare. However, winds and high humidity in a marine environment result in considerable chill factors making it a serious challenge for prisoners who are ill-fed, ill-clothed and ill-used merely to stay alive.

For six winter months of the year, the islands are practically isolated and the sea surrounding them is chock full of ice floes. Solzhenitsyn wrote, It was such a good place [for a prison], cut off from communication with the rest of the world for half a year at a time. You couldn't be heard from there, no matter how loud you shouted.

Solovky summers are normally very short, windy and rainy. Average summer temperature does not exceed plus 12°C (54°F), with peaks occurring up to plus 15°C (60°F) in September. Similar to Dawson City (Yukon, Canada), or Tok (Alaska, USA), there is nearly permanent daylight. The longest day in June lasts 21 hrs 56 min; exactly as long as the longest night in December. Mosquitoes are likely a considerable and ever-present pest, as is typical of all arctic and sub-arctic regions. From the report of rainy summers, one may infer the likelihood of considerable snowfalls in winter, it being humid year-round.

Although Solovkian conditions had been judged to be too severe and they ceased to be used as a prison by 1905, the Communists inherited the monastery's prison tradition, put it back into operation, and refined it into a much deadlier version. Under the frenzy of the Russian Revolution of 1917 the monks were ejected, the religious aspects were abolished, and the islands, monastery, and service buildings came to be dedicated strictly to prison, extermination, and forced labour use.

The Solovky Special Purpose Camp, the Auschwitz of the Arctic Circle in the Soviet Union under the acronym SLON -- standing for "Solovetskii Lager Osobogo Naznacheniia" -- with two distribution stations, one in Arkhangelsk and the other in Kem, was formally proclaimed by the 13 October 1923 decree of the Soviet Council of People's Commissars. It operated thereafter at full throttle as a colossal death complex for 16 years, earning the dubious distinction of being the forerunner and prototype of the entire USSR prison and extermination system ultimately known as the GULAG.

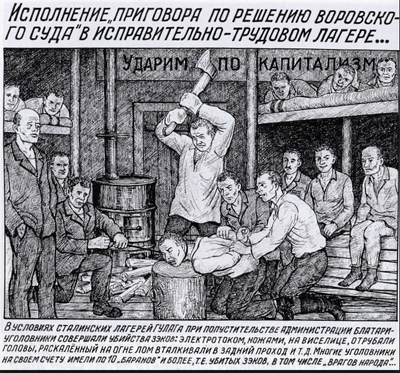

Penal servitude in Solovky in Soviet times had been characterized by people of that era as a "miniature Soviet Union". This was an accurate analogy not only because all nationalities of the USSR were represented there -- the entire geographic and national spectrum, from Moscow to the to the farthest reaches of the former Soviet Union -- but also because the repressive policy in Solovky mirrored the ongoing "repressions of the day" everywhere else in the country. The amplitude of repressions throughout the Soviet Union was instantly reflected in the mix and numbers of prisoners and the administration's attitude toward them.

One notes from this picture that women were also inmates of Solovky; they were not spared.

With Ukrainians having been the largest minority by far in the Russian Empire and in the subsequent USSR, a "Ukrainization" of the Solovky complex which began as early as the 18th century under the tsars, was briskly accelerated under the Soviets.

In earlier history, the most illustrious Ukrainian prisoner was Hetman Petro Kalnyshevsky, the leader of the legendary Ukrainian Zaporozhian Sich host of Cossacks, destroyed under Catherine II. Kalnyshevsky, taken prisoner, was banished to Solovky in 1776 and spent the remaining 26 years of his life in a narrow, dark and dank cell in solitary confinement. He died at age 110. Under the Soviets, no one was given the chance to live anywhere near that long.

There was no social category that would not be represented in Solovky. It was a true unity of all the peoples. The first waves of Solovky prisoners included activists of the Ukrainian National Republic and captured troops from the failed Ukrainian struggle for independence against Muscovy and Poland in the early 1920s, and commanders and members of numerous insurgent formations.

Later, the prison population was swelled by workers dissatisfied with their slave-like situation, peasants driven to despair in the collective farm "paradise," persecuted clergymen, then "specialists," i.e., representatives of the old intelligentsia who had been proclaimed "wreckers" and "bourgeois nationalists," and finally those individuals on whom the government had recently relied and whom it had exploited but who were now proclaimed "enemies of the people": Soviet writers, scientists, artists, poets, playwrights, academics.

All of them, with only a few exceptions, were doomed to die by the very fact that they were brought to Solovky.

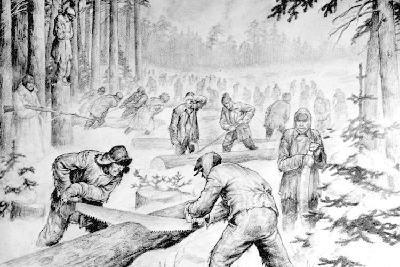

Inmates of Solovky chopped down and trimmed trees, manhandled felled tree trunks on turbulent waters to drag them ashore, drained marshes, laid railroad tracks, excavated rock with pick and shovel, and did massive earthmoving without any mechanized equipment but exclusively by makeshift rickety wheelbarrows to build the ill-famed Belomorkanal (White Sea - Baltic Sea Canal) 227 km (141 mi) long, which claimed the lives of nearly 100,000 prisoners and ultimately failed to win Stalin's approval (because "too narrow").

A prisoner's account of Solovky logging operations (Prisoner B.Sederkholm): prisoners enter into the water up to the throat during September, the end of autumn on Solovky and push slippery logs to shore by hand. It is real torture, to drag this slippery wet log, to stumble grasp bushes. Only death can free you from the work.

Author Semen Pidhainy writes of one woman who was assigned to such work in neck-high fast-running water.

Since the vast majority of prisoners condemned to Solovky had to die, all sorts of tortures, barbarities, rapes and mass killings were practiced on them freely. These depredations became routine and, like a cancer, metastasized across the Soviet Union into the odious "Archipelago" of Solzhenitsyn's metaphor. It is said that the number of Gulag camps increased ultimately to approximately 10,000.

The operation of the camp was assigned by the aforementioned Commissars' decree to the Unified State Political Administration (the OGPU) of the USSR, later known through progressive name changes as the NKVD, NKGB, MGB, MBS, KDB, MSB, AFB, MB, FSK and now the contemporary FSB.

Like the state's organs of repression, the Solovky prison complex SLON also underwent name changes over the years until, on Nov. 2, 1939, the OGPU issued a decree "On Closing the Prison of the Main Administration of State Security on Solovets Island." From 1939 to 1957, the islands were used by the Soviet navy's Northern Fleet for training purposes, following which, they seem to have lain idle for some years.

There is speculation that Stalin shut down Solovky death camp operations in 1939 out of fear that the Western nations would find out about it to his disadvantage, as the site is accessible from Finland. To be sure, the overall Gulag operations continued elsewhere unabated for many decades thereafter, accounting for the deaths of additional millions.

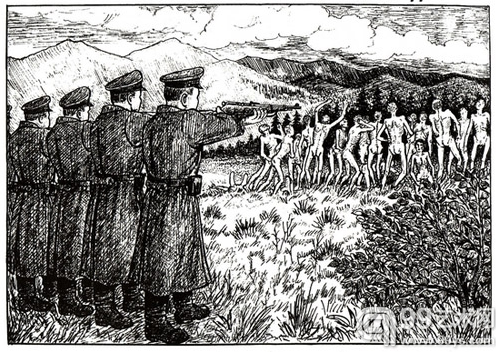

As recorded by a former inmate of the Gulag at Norilsk, Lev Netto, "Until 1953 shootings of inmates were a normal occurrence. After the death of Stalin there grew a feeling that this will stop, files will be reviewed and the hand of freedom will beckon us. But it became even worse, executions by shooting only increased. To others they painted us as animals, despots, there was a popular slogan: "Soldier, be alert to what it is you are guarding!" One could be shot on any pretext at any moment. People's sanity collapsed, it was unsupportable: inmates mutilated themselves, threw themseves onto barbed wire prison fences, committed suicide, attempted escape. There was only one thought: go ahead and shoot - to live is impossible."

Pavel Florensky, priest and professor of mathematics and physics at the University of Moscow, one of the most famous prisoners at Solovky, honoured in his lifetime as Russia's Leonardo da Vinci at home and abroad, wrote: "The nature here, despite all the views, which cannot be called other than beautiful and unique, is repellent to me. The sea does not look like a sea; it is rather something either dirty white or black and gray. All the rocks were brought here by glaciers. All the hills are alluvial and made of glacial trash. Nothing is native to this place, everything came here from somewhere else, including people . . ."

Florensky was shot in December 1937, as part of a wave of shootings undertaken to reduce the prisoner population of Solovki. In that same wave was a group of 1,111 inmates, many prominent Ukrainians among them, who were killed in a manner that only recently came to light.

These prisoners, under formal sentence of death, were transported by sea to Kem on the nearby Karelian mainland, and then southward by train, a trip of about 15 hours (if non-stop) to Medvezhegorsk, Karelia, on a northerly bay of Lake Onega near the White Sea - Baltic Sea Canal (see the map above). From here they were driven to a tract of land called Sandormokh, where an OGPU Captain named Mikhail Matveev personally shot between 180 and 265 prisoners every day. He shot them, as one of the OGPU documents states, "quickly, accurately, and intelligently." Shortly thereafter, Matveev was himself shot: dead men tell no tales. Of course, the shootings throughout the entire system continued unabated.

Physically, Solovky is endowed by nature with a remarkable beauty and lays claim to a great deal of history, so much so that in 1967 a Museum Preserve was created, and in 1994 Solovky was designated a World Heritage Site by UNESCO, making the area a protected historical preserve.

However, Solovky's blood-drenched record as a place of bondage, cruelty, and hopelessness makes of it an accursed place. It will be remembered as such, with horror, forever.

The author of the book that is being offered here was sentenced to Solovky in 1933, in the period when the islands were at their most febrile as a death camp, and in the very same year that Stalin was putting to death 10 million Ukrainians in Ukraine (and elsewhere) through the genocidal process of artificial starvation now known universally as the Holodomor. Sentenced to eight years' hard labour at Solovky, he was one of the very few with the extraordinary stamina and good fortune to survive and serve out his term, and obtain release from the camp into a sort of twilight zone of ersatz liberty. Twilight and ersatz, because former concentration camp inmates had to present themselves at the local police station once every week and were prohibited from ever living in cities, so how to earn a living?

Here I must let Mr. Pidhainy tell his own story in this most engrossing book so rich in historical vignettes, which he wrote after having successfully fled the bolsheviks in 1943, and gained admittance to Canada and to freedom in 1949.

Mr. Pidhainy, while working as a journalist and publicist, founded in 1950, in Toronto, Ontario, the Ukrainian Association of Victims of Russian Communist Terror and was president, until 1955, of the World Federation of Political Prisoners. He was also Editor-in-Chief of The Black Deeds of Kremlin: A White Book which contains testimonies of 350 individuals who had been victims of bolshevik crimes in the Soviet Union; and edited The New Review: A Journal of East-European History. In the Ukrainian language, he wrote the books Ukraiinska Inteligentsiya na Solovkakh (Ukrainian Imtellectuals in Solovky), 1947, and Nedostriliani (The Un-shot), 1949, also about Solovky.